m a s q u e s

Masks

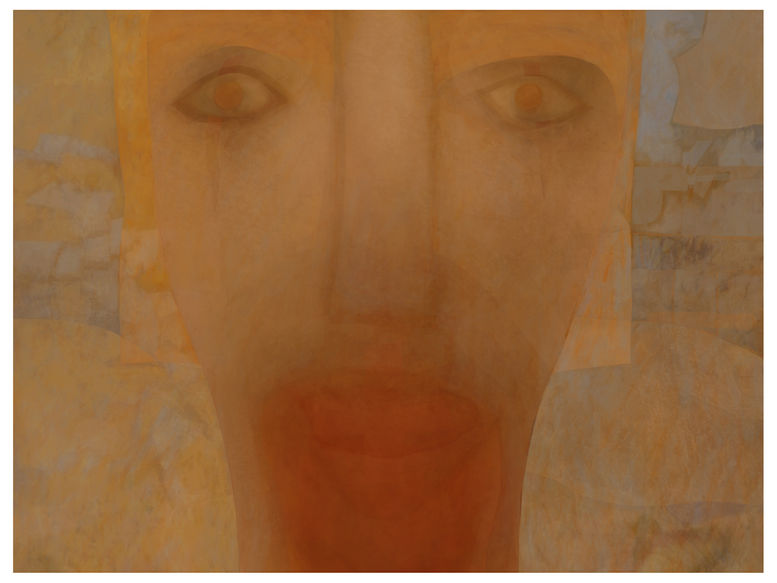

The perceptive observer will be instantly struck by the sacrilegious nature of this series of work entitled “ Masks” by Michael Pettet. For there is more than just a casual illusion in the translucent and strangely beautiful images to one of the most sacred, yet ultimately fraudulent, relics of Christendom, the Turin Shroud.

The title of Pettet’s work itself linguistically implies deception and duplicity. Pettet’s replication of the Christ like faces in the portraits questions the claim that the Turin Shroud represents the one and true likeness of Christ and, by doing so, Pettet exposes the deliberate and shameless exploitation by the Church of an image of Christ for the purpose of mass-consumption and ignorance. Alternatively, Pettet’s technique of replication could even suggest that, despite the Church’s veneration and mystification of the physical identity of Christ, the debate provoked by the authenticity of the Turin Shroud is ridiculous since every human being deserves the right to be revered and remembered. There is logic on Pettet’s side since after all does not the Bible itself state that every single one of us was made in Christ's image, the physical form that was adopted when he walked among us with his message of eternal life. One can sense that for Pettet this is not just an issue with the arrogance of the claim that the Turin Shroud represents the unique identity of Christ but with the way that religion insists on blind acceptance as the basic premise of faith. This series of portraits denies not just the existence of Christ but organised religion’s simplistic teaching on the whole mystery of human existence. By so irreverently questioning the identity of the individual whose face adorns the Turin Shroud, Pettet in turn challenges the whole premise at the centre of the Christian message that Christ came to earth and was crucified in order to save humanity from its sins.

For Pettet it is impossible to accept such claims even if this means forfeiting the prize of salvation and eternal life. Creation in his eyes did not start within the tame confines of the Garden of Eden with the relatively minor transgressions of woman and man. His vision is of a primeval universe of overwhelming and frightening cosmic dimensions. The comfort of an all-controlling god with a human face who can be visualised, and who has the power to forgive sin and offer eternal salvation, is not an option. The perplexing questions of our existence cannot simply be explained away by the blind acceptance that organised religion, a relative latecomer onto the scene, insists upon. Religion is not so much opium of the people that calms and soothes and induces forgetfulness. To Pettet it is entirely something more sinister. There are in these portraits reminders of the cruelty of the Inquisition in the searing and branding red cross that tries to silence. Elsewhere it seems that lips are crudely sown and sealed together in order to control those free thinkers who have tried to speak out and question throughout the ages. Elsewhere eyes are sliced and individuals left blinded to wander the dusty earth in perpetual punishment without the hope of salvation.

While there is undoubtedly anger in this work against the deception and cruelty of religion, there is also a quiet understanding of what it really means to be human. Pettet’s masks, unlike the Church’s Turin Shroud, do not hide and deceive, as the fragility of humanity is revealed in all its rawness in the imaginary portraits. That these images are medieval in style is a deliberate play on the real date of the Turin Shroud, despite clerical claims to the contrary, but to Pettet such minute timescales are essentially irrelevant. The entire duration of human existence is but a pinprick in the enormous span of eternity. Nevertheless, such is the vanity of our species that we try to explain and endlessly theorise about the meaning of our existence.

Yet Pettet does not condemn the hope that we entertain that our existence matters, that we are worthy of being saved by the coming to earth of the Superman of Christendom. These portraits are not the obvious jewelled skulls of Damien Hurst with his simplistic and brutal message of the finality of death and the futility of power and wealth in the face of it. The faces that stare out at us are very much alive. These are not eyes closed in death but desperate to make contact, with us the living, to be remembered. There is a lack of certainty about the final journey and the loneliness of the path that will return us to our original state. There is a yearning to understand and for the offer of a final comfort that all ultimately will be well. There is an intimacy and compassion in this series of imagined portraits by Pettet: a desire to connect and to explore humanity’s greatest fears.

Yet while the eyes are alive on closer examination there is no doubt that each face is a collective of evolved identities made up from the tissues of countless generations that have walked upon this earth in the past. We as individuals are a composite collection of all that has passed. Some of the faces in the series are in the process of dissolving into the genetical pool from which all original life came. Some barely seem human at all and are almost animalistic in form… pagan entities. They are finally and undeniably a bitter reminder that our species for all its cultural achievements, our ability to communicate, to question and to dream, is but mortal. Our ultimate fate will be no different from the soulless and dumb four-legged beasts that we biblically, were given indefinite dominion over for the duration of time.

“And God said, Let us make man in our image, after our likeness: and let them have dominion over the fish of the sea, and over the fowl of the air, and over the cattle, and over all the earth, and over every creeping thing that creepeth upon the earth.

So God created man in his own image, in the image of God created he him; male and female created he them.” (Genesis 1:26-7)

Dominic Simmons

19 February 2014